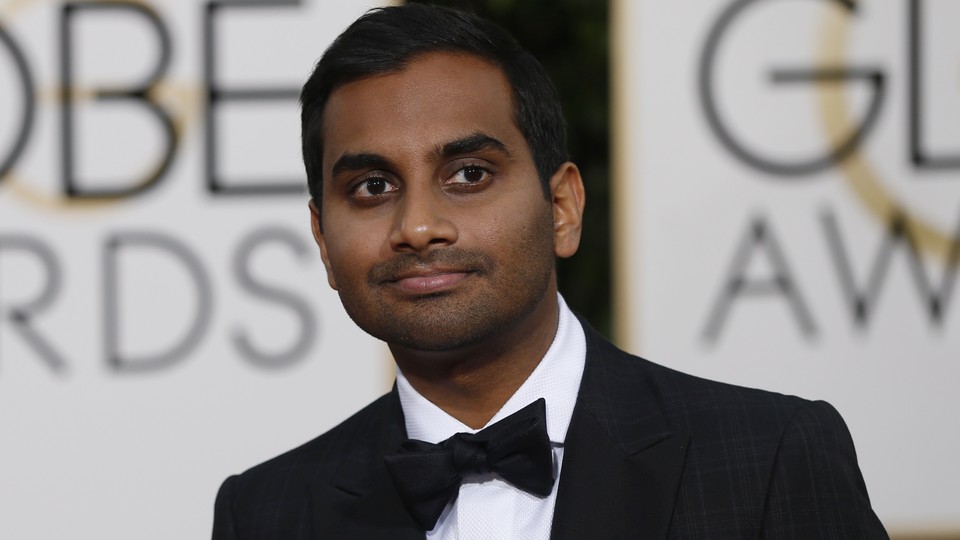

The Humiliation of Aziz Ansari

Allegations against the comedian are proof that women are angry, temporarily powerful—and very, very dangerous.

Sexual mores in the West have changed so rapidly over the past hundred years that by the time you reach 50, intimate accounts of commonplace sexual events of the young seem like science fiction: You understand the vocabulary and the sentence structure, but all of the events take place in outer space. You’re just too old.

This was my experience reading the account of one young woman’s alleged sexual encounter with Aziz Ansari, published by the website Babe this weekend. The world in which it constituted an episode of sexual assault was so far from my own two experiences of near date rape (which took place, respectively, during the Carter and Reagan administrations, roughly between the kidnapping of the Iran hostages and the start of the Falklands War) that I just couldn’t pick up the tune. But, like the recent New Yorker story “Cat Person”—about a soulless and disappointing hookup between two people who mostly knew each other through texts—the account has proved deeply resonant and meaningful to a great number of young women, who have responded in large numbers on social media, saying that it is frighteningly and infuriatingly similar to crushing experiences of their own. It is therefore worth reading and, in its way, is an important contribution to the present conversation.

Here’s how the story goes: A young woman, who is given the identity-protecting name “Grace” in the story, was excited to encounter Ansari at a party in Los Angeles, and even though he initially brushed her off, when he saw that they both had the same kind of old-fashioned camera, he paid attention to her and got her number. He texted her when they both got back to New York, asking whether she wanted to go out, and she was so excited, she spent a lot of time choosing her outfit and texting pictures of it to friends. They had a glass of wine at his apartment, and then he rushed her through dinner at an expensive restaurant and brought her back to his apartment. Within minutes of returning, she was sitting on the kitchen counter and he was—apparently consensually—performing oral sex on her (here the older reader’s eyes widen, because this was hardly the first move in the “one-night stands” of yesteryear), but then went on, per her account, to pressure her for sex in a variety of ways that were not honorable. Eventually, overcome by her emotions at the way the night was going, she told him, “You guys are all the fucking same,” and left crying. I thought it was the most significant line in the story: This has happened to her many times before. What led her to believe that this time would be different?

I was a teenager in the late 1970s, long past the great awakening (sexual intercourse began in 1963, which was plenty of time for me), but as far away from Girl Power as World War I was from the Tet Offensive. The great girl-shaping institutions, significantly the magazines and advice books and novels that I devoured, were decades away from being handed over to actual girls and young women to write and edit, and they were still filled with the cautionary advice and moralistic codes of the ’50s. With the exception of the explicit physical details, stories like Grace’s—which usually appeared in the form of “as told to,” and which were probably the invention of editors and the work product of middle-aged women writers—were so common as to be almost regular features of these cultural products. In fact, the bitterly disappointed girl crying in a taxi muttering, “They’re all the same,” was almost a trope. Make a few changes to Grace’s story and it would fit right into the narrative of those books and magazines, which would have dissected what happened to her in a pitiless way.

When she saw Ansari at the party, she was excited by his celebrity—“Grace said it was surreal to be meeting up with Ansari, a successful comedian and major celebrity”—which the magazines would have told us was shallow; he brushed her off, but she kept after him, which they would have called desperate; doing so meant ignoring her actual date of the evening, which they would have called cruel. Agreeing to meet at his apartment—instead of expecting him to come to her place to pick her up—they would have called unwise; ditto drinking with him alone. Drinking, we were told, could lead to a girl’s getting “carried away,” which was the way female sexual desire was always characterized in these things—as in, “She got carried away the night of the prom.” As for what happened sexually, the writers would have blamed her completely: What was she thinking, getting drunk with an older man she hardly knew, after revealing her eagerness to get close to him? The signal rule about dating, from its inception in the 1920s to right around the time of the Falklands War, was that if anything bad happened to a girl on a date, it was her fault.

Those magazines didn’t prepare teenage girls for sports or STEM or huge careers; the kind of world-conquering, taking-numbers strength that is the common language of the most-middle-of-the road cultural products aimed at today’s girls was totally absent. But in one essential aspect they reminded us that we were strong in a way that so many modern girls are weak. They told us over and over again that if a man tried to push you into anything you didn’t want, even just a kiss, you told him flat out you weren’t doing it. If he kept going, you got away from him. You were always to have “mad money” with you: cab fare in case he got “fresh” and then refused to drive you home. They told you to slap him if you had to; they told you to get out of the car and start wailing if you had to. They told you to do whatever it took to stop him from using your body in any way you didn’t want, and under no circumstances to go down without a fight. In so many ways, compared with today’s young women, we were weak; we were being prepared for being wives and mothers, not occupants of the C-Suite. But as far as getting away from a man who was trying to pressure us into sex we didn’t want, we were strong.

Was Grace frozen, terrified, stuck? No. She tells us that she wanted something from Ansari and that she was trying to figure out how to get it. She wanted affection, kindness, attention. Perhaps she hoped to maybe even become the famous man’s girlfriend. He wasn’t interested. What she felt afterward—rejected yet another time, by yet another man—was regret. And what she and the writer who told her story created was 3,000 words of revenge porn. The clinical detail in which the story is told is intended not to validate her account as much as it is to hurt and humiliate Ansari. Together, the two women may have destroyed Ansari’s career, which is now the punishment for every kind of male sexual misconduct, from the grotesque to the disappointing.

Twenty-four hours ago—this is the speed at which we are now operating—Aziz Ansari was a man whom many people admired and whose work, although very well paid, also performed a social good. He was the first exposure many young Americans had to a Muslim man who was aspirational, funny, immersed in the same culture that they are. Now he has been—in a professional sense—assassinated, on the basis of one woman’s anonymous account. Many of the college-educated white women who so vocally support this movement are entirely on her side. The feminist writer and speaker Jessica Valenti tweeted, “A lot of men will read that post about Aziz Ansari and see an everyday, reasonable sexual interaction. But part of what women are saying right now is that what the culture considers ‘normal’ sexual encounters are not working for us, and oftentimes harmful.”

I thought it would take a little longer for the hit squad of privileged young white women to open fire on brown-skinned men. I had assumed that on the basis of intersectionality and all that, they’d stay laser focused on college-educated white men for another few months. But we’re at warp speed now, and the revolution—in many ways so good and so important—is starting to sweep up all sorts of people into its conflagration: the monstrous, the cruel, and the simply unlucky. Apparently there is a whole country full of young women who don’t know how to call a cab, and who have spent a lot of time picking out pretty outfits for dates they hoped would be nights to remember. They’re angry and temporarily powerful, and last night they destroyed a man who didn’t deserve it.